Partnership and collaboration in European projects

Working in a complex world

In previous chapters we have placed special emphasis on the technical dimension of projects, that is, how to design and structure them effectively, how to analyze problems and available intervention options, and how to develop meaningful activities and indicators.

As already mentioned, this is not an “autarkic” process, but a work that starts from a thorough analysis of the reference context and the actors operating in it. We have proposed, for this purpose, some tools such as stakeholder analysis, SWOT analysis and “spider web” diagrams.

In this new chapter we want to delve more deeply into the “social” dimension of projects.

European projects are in fact large “group works” that require continuous interaction between people, groups and organizations, both in conception and implementation. This makes it possible to broaden the scope and quality of interventions, learn from each other and innovate, but it also represents an element of additional complexity that can generate stress and grounds for potential conflict. The cooperation and coordination aspects can absorb a lot of energy (positive and negative) and are a crucial determinant of success (or failure) in European projects.

We therefore provide, below, some suggestions and tools to better manage these aspects.

Other more practical insights related to the same topic are addressed in the following chapters: Preparing for the project | Presenting a project | Reporting in European projects.

Partnership and collaboration: asking the right questions

When participating in a European project, each organization maintains its mission, values, needs, current activities and priorities. Participating in a European project is an additional commitment and deployment of additional energy. Therefore, it is important to engage the right partners whose interests are aligned with those of the project and who have the prerequisites to maintain the required commitment. To this end, the following aspects should be evaluated and the following questions should be asked.

- Relevance. Is the partner relevant to the sector and the project activity? Do you bring resources, skills, or specializations that are useful in making it happen? Is your involvement and participation necessary? Or conversely, is it necessary to involve other partners to have the expertise and resources that are needed for the project? In addition to technical expertise, does the partnership (and particularly its lead partner) have sufficient experience in managing European projects?

- Diversity. Does the project and its animating partners bring varied and complementary professional experience and input? A project with too “routine” intents or too homogeneous partnership is unlikely to stand out, create something new and drive change.

- Opportunities. What is the optimal size of the partnership? There is a need to identify the “trade off” between the need to include resources and expertise and the need to avoid too many partners, which implies too much coordination effort. Is the demarcation between partners’ areas of specialization and responsibility clear, or is there obvious duplication?

- Risks and critical issues. What mission and interests does each project partner have? Are there possible sources of conflict or rivalry between the partners? Are there asymmetries between partners in terms of power, resources, and capabilities? Are the benefits of collaboration on the project enough to overcome any obstacles? Are there more appropriate forms of collaboration and partnership management to remove or eliminate them?

- Governance. How and by whom are decisions about project activities and resources made? Do the people assigned enjoy the esteem, trust, and consent of the entire partnership? Are they able to understand and manage the different sensitivities and organizational forms of project partners? Are they suitable for guiding the changes that necessarily occur during the life of a project? Is there a monitoring and reporting system, data and rules to guide decisions and allocation of common resources? Is there adequate space for negotiation between partners to express and affirm different opinions?

These aspects must be kept in mind when creating the partnership and preparing the document that summarizes the mutual commitments between the partners, namely the partnership agreement.

Similar considerations can be extended outside the partnership. Actors not involved in the partnership may in fact benefit, participate, collaborate or act synergistically with respect to project activities. Stakeholder mapping makes it possible to identify all the organizations that orbit the project, are involved in it or can appreciate its results, and to place them in different and functional roles in the project activities, not necessarily in the role of partners.

There is also a life and relationships of the project outside the partnership: through the proposed questions, appropriately adapted to different situations, it is possible to assess which actors should actually be included in the scope of the project, or left out, to ensure a good interaction between the project and its surroundings.

Clarifying goals and strategies, thinking about the "system"

Partnership is therefore a necessary element in almost all European projects, but it should not be a “forced marriage.” Good collaboration comes from clear, common and shared goals, strategies and expectations. A misalignment on these basic aspects can lead to delays and problems in the implementation of activities, on the workload of other partners (especially the lead partner), on project results, and on the disbursement of funding. Alignment between partners can be assessed through the following questions.

- Vision. Do the project partners have a common vision of the change they want to achieve, both in general and through the project? Do they have common goals and interests on which to build their collaboration and project?

- Expectations. Do partners have similar expectations about what the project could bring them (benefits, learning, impact on their business and industry) and do they see it as commensurate with the commitment and resources they will have to devote to it?

- Agenda. Is the general alignment in danger of not materializing because of specific points that may create tension? For example, rivalry or competition between organizations, possible divergent evolutions in the way they work, hostility or lack of commitment from specific people?

- Strategy. Do the goals and project enhance and develop the strengths of the partners? Does the project respond to problems and help resolve weaknesses that partners actually feel in their business or sector? Does the project harness opportunities and energies that they perceive as important to create a common “leverage effect”?

- Energy. Is the project able to keep the “energy” level of partners and stakeholders high, right from the start and throughout its duration? Can it create immediate (or at least ongoing) positive results and shared “success stories” that build mutual trust and motivation to continue?

These questions, and generally what project partners apply to each other, must also be convincingly answered in the relationships between the project, its stakeholders and other organizations working in the field, at all levels:

- The vision, is it a vision that is shared (or can be shared) by community institutions, by European actors in the sector, by actors in the area where the partners operate, by those who work in the sector, and by those who should benefit from the project results? Or, on the contrary, can we expect skepticism, contrariness, or adverse reactions from some of them?

- Do the partners’ expectations contemplate added value and a positive effect even as a whole, for the “system” in which the organization operates (at the sectoral, local and European levels)?

- Could the partners’agenda regarding the proposed project conflict with what some individuals, organizations, or institutions would or could achieve?

- Is the strategy convincing even to non-participants because it develops interesting points, resolves weaknesses that others also feel, and can extend its effects on a large scale?

- Is theenergy created by the project also transmitted to those who experience it from the outside, as beneficiaries, collaborators, sympathizers, or mere observers? A successful project is able to create growing consensus and collaboration (and why not, a process of imitation) in an area or subject area.

It is difficult to come up with a project that everyone, universally and across the board, is enthusiastic about and from which everyone receives a benefit: one must properly choose one’s “target audience” and one’s target audience. If the project can create doubts or resistance, and these do not have to do with the intrinsic value from the project, but can have a negative impact on its implementation, corrective measures, involvement and awareness-raising should be introduced.

We propose below some tools to help analyze in more depth possible situations of conflict and collaboration, within and outside the project partnership, in order to manage them appropriately in the preparation phase and during the operational life of the project.

The "Seven Cs" theory

The first conceptual tool we propose takes its cue from biology:

“The form of interaction between two or more living beings can be schematized into the seven different types described in the diagram and beginning with “C.” This structure is useful for defining not only the relationship of the different stakeholders in a system and the relationship between them and those outside the system, but also for defining the type of interaction the external stakeholder will have with each of the local stakeholders.” (Source: J. Schunk, The project cycle, January 2022).

- Competition. There is a conflict between the parties. One side seeks an advantage over the other and must prove stronger than the other. Struggle is necessary for survival.

- Cohabitation. There is balance and mutual autonomy. There is no struggle or interference. The power between the parties is similar and each can live without the other.

- Coordination. The parties survive without each other and maintain their own behaviors and positions, but have convenience in helping each other (e.g., with information).

- Cooperation. The needs of the parties require rapprochement, negotiation, and adapted behavior (on both sides). One side needs the other to survive.

- Complementarity. Full integration (or merger) between the parties. Each side thinks of the common benefit before its own. Belonging to a common entity is necessary for survival.

- Control. One (weaker) party loses its autonomy because the other (stronger) party exerts a form of control over it.

- Conditioning. Manipulation of one party by the other, through various forms of conditioning (physical, economic, moral, psychological, etc.).

Clearly, Coordination and Cooperation are the typical dimensions of a project, but in every project (as in every human and natural interaction) there is room for all possible modes. It is important to recognize them, overcome possible over-optimistic views (collaboration is not the only possible form of interaction) and evolve relationships, both during the preparatory phase of the project and during and after its operational life. European projects have among their purposes to bring about and evolve relationships between actors in a sector and territory.

The mapping of actors: methods of analysis

Actor mapping, or stakeholder analysis, can be implemented through various methods. One has already been proposed in the previous chapter and provides, for each organization, a brief description:

- Of the organization itself,

- Of the interests and problems involving it,

- Of its capabilities and possible stimuli for change,

- Of the possible actions that can be used to arouse their interest.

The matrix that emerges from this analysis can be used in a variety of ways: as a descriptive, strategic and operational tool; as a plan of activities to clarify mutual expectations and priorities; and to ensure smooth functioning of the project, among partners and with the surrounding world.

There are other, equally effective and complementary versions of stakeholder analysis matrices. Some interesting examples have been adopted from the German cooperative project management system. One of these is the 4A matrix, which presents:

- a brief description of each Actor (the first “A” in the matrix),

- its Agenda (i.e., its mission, goals and likely strategic evolutions),

- its Arena (i.e., the specific context in which it operates, the area in which it has a reputation and can exercise ability and influence),

- its Alliances (i.e., the relationships it has with other actors, positive and negative, relevant to the project).

Another example is the PLAN matrix, which is not about all actors but only about the partners in a project as a group. In preparing a PLAN matrix, partners jointly analyze the following aspects:

- The Products (P), which are the concrete outputs they intend to achieve together,

- the Incentives (I), or the benefits and expectations that motivate each of them to participate in the project,

- The Actors (A), i.e., the specifics of each partner’s mission regarding the intended joint project,

- the Negotiations (N), which are the rules of internal communication, project management, accountability and decision-making that govern the relationships among partners,

- The Guidelines (O), which is the common vision that the partners intend to adopt on the project, felt and shared among all.

The matrix can be drafted in multiple sessions and at multiple times, because one of its purposes is to bring out possible conflict or disagreement elements that need to be resolved.

Actor mapping: a graphical representation

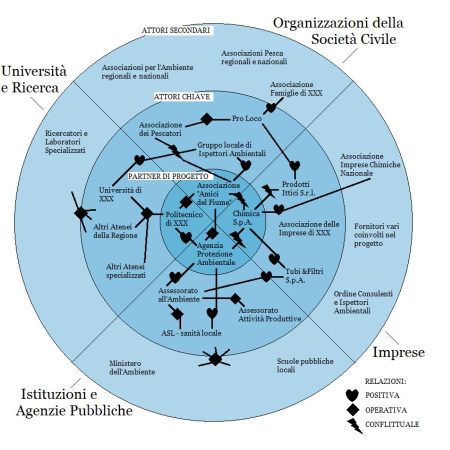

A specific circular diagram, known as a “bull’s-eye,” is used to visually represent the variety of actors active on a project, their membership and the nature of their relationships.

- Sectors of the “eye” can be used to identify the nature of the partner or actor (e.g., private sector, public institutions, and civil society) or its area of intervention (e.g., education, youth work, and communication).

- The concentric circles of the “eye” can be used to identify the degree of proximity to and involvement in the project of each of the actors, for example: project partners in the innermost circle; key actors directly involved in the project in the middle circle (groups-targets or entities that benefit from the project, collaborate directly with it, or have an operational or decision-making impact on it); secondary actors in the outermost circle (actors whose relationship to the project is only indirect and temporary).

- Actors can then be connected to each other with lines that identify their type of interaction with each other, for example using the types illustrated in the more above (the “Seven Cs”), or a simpler version of them.

- Finally, each actor can be identified by a symbol that illustrates its nature, area of intervention, role or relationship to the project, in place of the previously listed graphic solutions (should their simultaneous use be unclear and ineffective or additional features need to be highlighted).

The diagram below provides an example of how to carry out simple stakeholder mapping, starting with the case study proposed in the previous chapter: a hypothetical project to benefit a poor river community whose economic (fishing revenues) and environmental (citizen health) balance is threatened by river pollution.

In this example, a large company, a university, a local association and agency come together in a partnership to test new water filtration and treatment systems. What emerges from the diagram?

- On the one hand, it is possible that the diversity of the partnership (bringing together organizations with very different goals and visions) is an element of seriousness and helps build consensus around the project. Each partner can enhance its “social capital,” its expertise and its good relations with actors in a specific area. The complementarity between partners is very high and is functional to the perimeter of actors with whom the project can (and will) interact, which is very diverse and extensive.

- On the other hand, there is a risk that the diversity of partner organizations, combined with possible rivalries and incompatibilities existing at the local level, will create an unstable and conflicting basis for joint project development and management. There is a risk that the small association will find itself isolated within the project partnership in terms of operational capacity, relationships, and decision-making clout. Major work is needed to define common vision, goals, activities and objectives, and to build a participatory and effective project management structure.

To enlarge, click on the image.

Assigning roles and responsibilities

Once the partnership has been identified and the forms of collaboration and interaction with other actors active in the sector and in the area clarified, it is necessary to assign them roles and responsibilities. This can be done as project activities and reference “work packages” are defined.

A first step is to accompany each of the activities listed in the classic Gantt chart with a quantification of the material resources and work days required. The outline can be expanded and detailed as activities and approaches are more specifically defined. It should be constructed in parallel with the project budget (the topic is discussed in more detail here and elsewhere in this section).

Next, the practice of European projects (borrowed from organizational science) involves the development of a “responsibility assignment matrix.” These matrices (there are several types) cross-reference the list of project activities with the set of key figures of the project (and/or its partners).

For each activity, it is defined which figure is (or are) in charge of a specific aspect related to that activity. The size of analysis can change depending on the type of matrix used. The most common include the following: their names stand for the identified levels of responsibility.

- The “RACI” matrix requires identifying for each activity who is Responsible[R] (in charge of performing it), Accountable[A] (responsible for its execution), Consulted[C] (committed to collaborate and help), and Informed[I] (kept abreast during execution and informed upon completion of the activity);

- The “PARIS” matrix requires identifying for each activity who is Participant[P] (participates in the execution of the activity), Accountable[A] (is ultimately responsible for it), Review required[R] (is required to give a technical evaluation of it), Input required[I] (is required to provide technical input), and Sign-off required[S] (is required to give a final and formal approval);

- The “RAPID” matrix requires identifying for each activity who is to Recommend[R] (provide the necessary elements for a decision), Agree[A] (formally make the decision), Perform[P] (carry out what was decided), Input[I] (provide elements and information needed by other functions), Decide[D] (be responsible for the action and assign responsibilities).

How to use these tools

Similar tools to those mentioned are also found in the European Commission’s proposed OpenPM2 Guide and the user materials it provides.

They are tools designed to be used, for example, in meetings or workshops where the opportunity to develop partnerships and joint projects is discussed; or as the basis for shared documents in which the partnership’s potential, needs and directions are expressed.

More than a value in themselves, these tools have value as a stimulus for reflection (and action) in building a good project partnership and in dealing with the unforeseen events of project life related to working together with other (sometimes very different) actors and people, in a complex surrounding world, in which one has to interact with a plurality of other initiatives, interests and organizations.

Partnership management and the Consortium Agreement

The relationship between partners in a project is governed by a document called a Partnership Agreement (Partnership Agreement) or Consortium Agreement (Consortium Agreement). We use “Consortium Agreement” because “Partnership Agreement” (or Partnership Agreement) is a designation that can refer to different documents (as indicated in our Glossary).

Entering into a Consortium Agreement may be mandatory under some European programs and calls for proposals, but there is no official or universal model Consortium Agreement, for several reasons. Indeed, European projects cover very different themes, sectors and types of activities, and may involve very different partners in terms of the type of organization, the commitments and responsibilities they may assume and the specific contractual arrangements they require. Moreover, since it is a document subject to many variables and regulating a relationship between private parties, the European Commission and the Managing Authorities do not impose, nor do they propose or suggest, specific reference models. In the Italian context there is a specific contractual form for the implementation of joint projects between Third Sector entities, the ATS (Associazione Temporanea di Scopo), which can be used to further formalize agreements made under a Consortium Agreement.

The closest document to an “official model” Consortium Agreement is proposed by an initiative called DESCA (Development of a Simplified Consortium Agreement ), which has developed a model Consortium Agreement considered comprehensive and reliable by the community of actors working on European projects and by the European institutions themselves.

The DESCA model is, of its kind, simple, comprehensive and relatively flexible, with several options, forms and alternative clauses. It is presented both in an editable version (Word document), and in a version that provides comments and clarifications on the proposed clauses (PDF document).

However, it was born in a specific frame of reference, that of the Horizon Europe program, for which it was specifically designed. This implies that it may be too specific and complex for other types of European programs, such as Erasmus+, Creative Europe or CERV. For these programs, however, the DESCA model can be a starting point and inspiration . Its different clauses, sections and options can be adapted (and in many cases simplified) based on the specific needs of the project and partners. After all, since it is a model, DESCA was born precisely to be modified and adapted, even and especially in case it is used for areas other than those for which it was developed.

We therefore use the main sections of the DESCA model to provide a basic idea regarding the most important and “classic” contents of a Consortium Agreement, with some advice taken from its “annotated” version. In the summary we provide below, we try to simplify the provisions of the DESCA model to make them more general and applicable to most projects.

It is advisable to sign the Consortium Agreement before signing the Grant Agreement (i.e., the contract that formalizes the project award and grant), and if possible to agree on its main aspects even before the proposal is submitted. Normally, a draft Grant Agreement (on the basis of which to set up various aspects of the Consortium Agreement) is available among the reference documents found (for example) on Funding&Tenders or among the attachments to the call for proposals.

1. Definitions and Purpose. First of all, it is necessary to agree on the terminology, keeping it in line with what is used within the program, the call and the Grant Agreement. Examples: definition of Project, Lead Partner, Associate Partner, etc. – to which should be added a definition of the most important aspects to regulate project activity and mutual ties between partners. Among the definitions cannot fail to include the purpose of the Consortium Agreement, which can be defined in a relatively standard way: to specify, with respect to the Project, the relationship between the Parties, particularly with regard to the organization of work between the Parties, the management of the Project, the rights and obligations of the Parties (mutual and with respect to the Project), and the resolution of disputes. In addition, at the opening of the document, it is appropriate to define the documents to which the Consortium Agreement is hierarchically and logically bound, such as the Grant Agreement, the call for proposals, and the regulations concerning the program and its management arrangements.

2. Entry into force, duration, and termination. These are important aspects as project activity is a “continuum” in which there may be little clarity on start and end dates of rights and obligations mutually assumed by the partnership. Again, it is recommended to align with dates, durations and constraints stipulated in the Grant Agreement, with a larger time window to include preparatory (e.g., project submission, provision of documents, resources and authorizations) and post-project activities (e.g., dissemination, continuation of activities, support in case of audits); and to provide specific conditions in case one of the partners intends to “exit” the project or is unable to continue its activities.

3. Responsibility of the parties and Mutual Responsibility. This section represents the “heart” of the Consortium Agreement. Several aspects need to be defined here: the general principles, responsibilities, and division of labor among the partners (e.g., referring to specific “Work Packages”); what to do in case of significant violations or deficiencies in the performance of one of the partners; and the specific conditions to be applied in the involvement of third parties, data protection, technical reporting, procedures, and administrative documentation. It is also necessary to define the extent and manner in which the project partners are mutually responsible to each other for the work performed, for the use of the project results, and for any damages, negligence, or violations produced in the performance of the project activity.

4. Governance structure. This section is very important and can be relatively long and detailed because it governs how the partnership will operate. The partnership may include, for example: a General Meeting of the members, which on the basis of a shared agenda and specific voting rules, discusses and makes decisions that are fundamental to the life of the project; a Coordinator or Lead Partner, who is the sole representative of the Consortium in its relations with the Awarding Authority, and whose responsibilities and constraints need to be defined; other possible structures with their own responsibilities and rules of operation, such as the Work Package Leaders Group (a more operational working and decision-making group composed of those with responsibility for one of the Work Packages) or the Expert Advisory Board (for advice and support on controversial or complex issues). Obviously, the complexity of the rules and structure of the partnership should be commensurate with the complexity and needs of the project.

5. Financial Provisions. This part defines the principles for the use of funds, which of course must follow what the project provides, in terms of how and when reports are approved and disbursed by the authority managing the funds. The partners must therefore be committed to ensuring good management (adherence to timelines, compliance with ceilings and types of expenditures, cash flows, supporting documentation, technical reporting), and monitoring and compensation measures must be in place in case of discrepancies and errors by one of the partners. Correspondingly, arrangements must be agreed on how the lead partner (the sole “receiver of funds” and the sole interlocutor vis-à-vis the managing authority) will make payments to the partners and how it will fulfill its obligations in the financial management of the project.

6. Management of results and information. Next, the partners must agree on how the results of the project and anything produced by it are to be attributed and used: in what cases attribution and use rests with the partner who produced them or with the partnership as a whole; in what cases and how they may be used (for any commercial or noncommercial purposes), transferred to third parties, or disseminated to the public. The same applies more generally to information accessed during the preparation and implementation of the project; to aspects of confidentiality; to the use of any technologies, software or databases produced or fed by the project; and to what provisions apply, on these matters, to any associated partners, external partners, beneficiaries and suppliers.

7. Concluding provisions. As with any contractual document, it is appropriate to define how formal communication (language, medium, attestation of sending and receipt) is to be used on aspects related to the Consortium Agreement itself (e.g., acceptance or requests for revisions, allegations of violations or withdrawal from the partnership), applicable law, venue, and how any disputes are to be resolved. It is important to provide for ways to agree on changes to the agreement and budget, as this is an eventuality that often occurs over the life of projects. Additional articles can, of course, be provided based on the needs of the partners, such as on issues of ethics and transparency or visibility, but these must always be in line with the provisions of the Grant Agreement. The list of annexes, which should be considered an integral part of the Consortium Agreement, should also be indicated.

8. Attachments. The number and nature of annexes can vary greatly, depending on the nature of the partners and the project. In general, it is appropriate to define in annexes: a) the type of contribution and resources provided by each partner, with any reservations and conditions to be applied at the time of project implementation and the subsequent phase of exploitation and dissemination of its results; b) the project budget, its timeline, planned activities, responsibility over the various Work Packages, and (if any) the Project Logical Framework; c) other salient parts of the project proposal; d) the main templates and tools to be used in the project (partnership membership, proxies to the lead partner, convening and minutes of meetings, reports, archiving and monitoring methods, software and platforms used, contact details of contact persons and their alternates, etc.).