Impact, a complex concept. The result of monitoring and evaluation activity is clearly and directly appreciable when it concerns operational aspects: activities and outputs realized, beneficiaries reached, and immediate and visible consequences of a project that has just been completed. These data, which are mainly obtained through monitoring activities, are also the most important for project implementers, who are held directly accountable.

It is, on the other hand, more complex to answer broader and more strategic questions typical of evaluation work: what was (and what will be) the impact of the project? Has the project achieved its ultimate goal, that is, its overall objective? Has it produced the effects and change it was intended to when it was developed?

Answering these questions with objective evidence requires collecting data in a period after the project has ended and using resources that may go beyond what is made available under a single European project.

Moreover, impact is a conceptually and statistically-mathematically complex concept because many factors contribute to its realization: it is not easy to “isolate” the project’s contribution from a plurality of other concomitant factors. For example: how appreciable are the effects of a poverty reduction project on a community, and how do we isolate them from a plurality of other factors (positive or negative) such as the effects of the economic situation, industrial policies, other parallel projects, and the initiative of community members?

However, measuring impact remains a legitimate concern: impact is an integral part of the project’s rationale and its monitoring and evaluation framework; it is the starting and ending point for anyone implementing or funding a project; it is what defines in the broadest terms the actual success of the project.

Again, the following discussion makes no claim to scientific rigor or comprehensiveness, but aims to translate the concept of “impact” into some insights that may be “within the reach” of European project implementers.

Impact as counterfactual analysis. Counterfactual analysis defines impact as the difference between data collected at the end of an intervention (“factual” data) and data collected in a situation characterized by no intervention (“counterfactual” data). This is the most “scientific” approach to impact evaluation: in fact, it is used in medical research, which compares “subject to treatment” groups with time series or control groups.

This approach is difficult to use in the social field, as it assumes:

- The existence of indicators that can be unambiguously verified with analytical tools and that have an equally unambiguous and long-term link to the dimension they are intended to measure;

- Or, the possibility of identifying a “control group” with characteristics and dynamics fully comparable with those of the project’s target group.

These are not easy conditions for many projects involving “human” and social aspects, where the correlation between data and measured phenomenon may be more or less strong, but is hardly unique and depends on the intervention of multiple factors (especially given the small scale of a normal project); and where the situations of groups and communities are very varied, complex and difficult to compare with the limited resources of a normal project.

Despite its operational limitations in the context of European projects, counterfactual analysis remains a useful “ideal reference” for measuring impact. It can be carried out with three mode modifications:

- The one called “Pre-post design”, which estimates impact from discrepancies between long time series of data (and resulting projections) and what is observed after project implementation. This mode requires a time span and scope of intervention that are difficult to match with the data and accomplishments of a project;

- The one called “control group design”, which estimates impact by analyzing the difference between the group of project beneficiaries and a “control group” with the same characteristics. This mode involves identifying (and analyzing) a control group that is “other” than the project activities;

- The one called “Difference in differences”, which combines the previous two modes and analyzes the double variation of a variable: over time (before, after, ex-post”) and between subjects (recipients and nonrecipients).

Impact as a change in a trend. Counterfactual analysis can be used in a mitigated form, adopting a less rigorous approach to dealing with project data and baseline trends, with the degree of complexity proportionate to the project’s ambitions and available resources. After all, if the group of “treated subjects” (i.e., project beneficiaries) concerns only (as is often the case) a few dozen people, a serious counterfactual impact assessment loses its meaning and scientific relevance.

The “trajectory change” in the estimated trend will therefore have a narrative and indicative value. However, it can be useful in producing some suggestions at the conclusion of a project, in combination with the more substantive elements of a report, related to more easily and objectively verifiable aspects (activities and outputs realized, beneficiaries reached, follow-up data on beneficiaries). To make impact estimation more realistic and truthful, we recommend:

- Circumscribe the scope of the phenomenon being measured to that to which the project contributed most strongly and directly (thus increasing the level of correlation between the indicator and the objective being measured);

- Compare the evolution recorded by project data against reference points as “close” as possible to the project population-target (a “quasi-counterfactual” situation);

- Combine different and complementary comparison references, if possible, by “triangulating” different data and viewpoints to increase the reliability of results;

- Include in the analysis, if possible, multiple moments of measurement (to set a trend), including “follow-up” measurements (e.g., after one, two or three years after the conclusion of the project);

- Accompany the analysis with an assessment of the factors (positive or negative) that may have influenced the data and “trends” of the project and the references used.

For example, on a project dedicated to job placement for young people in the 15-24 age group, residing in an urban local organisations subject to social problems, changes in employment data of young people in the 15-24 age group recorded can be compared:

- From the project on its beneficiaries (baseline vs. final data: “factual” data).

- In the project intervention area (or in another urban local organisations subject to social problems), during the same period (a “quasi-counterfactual” figure).

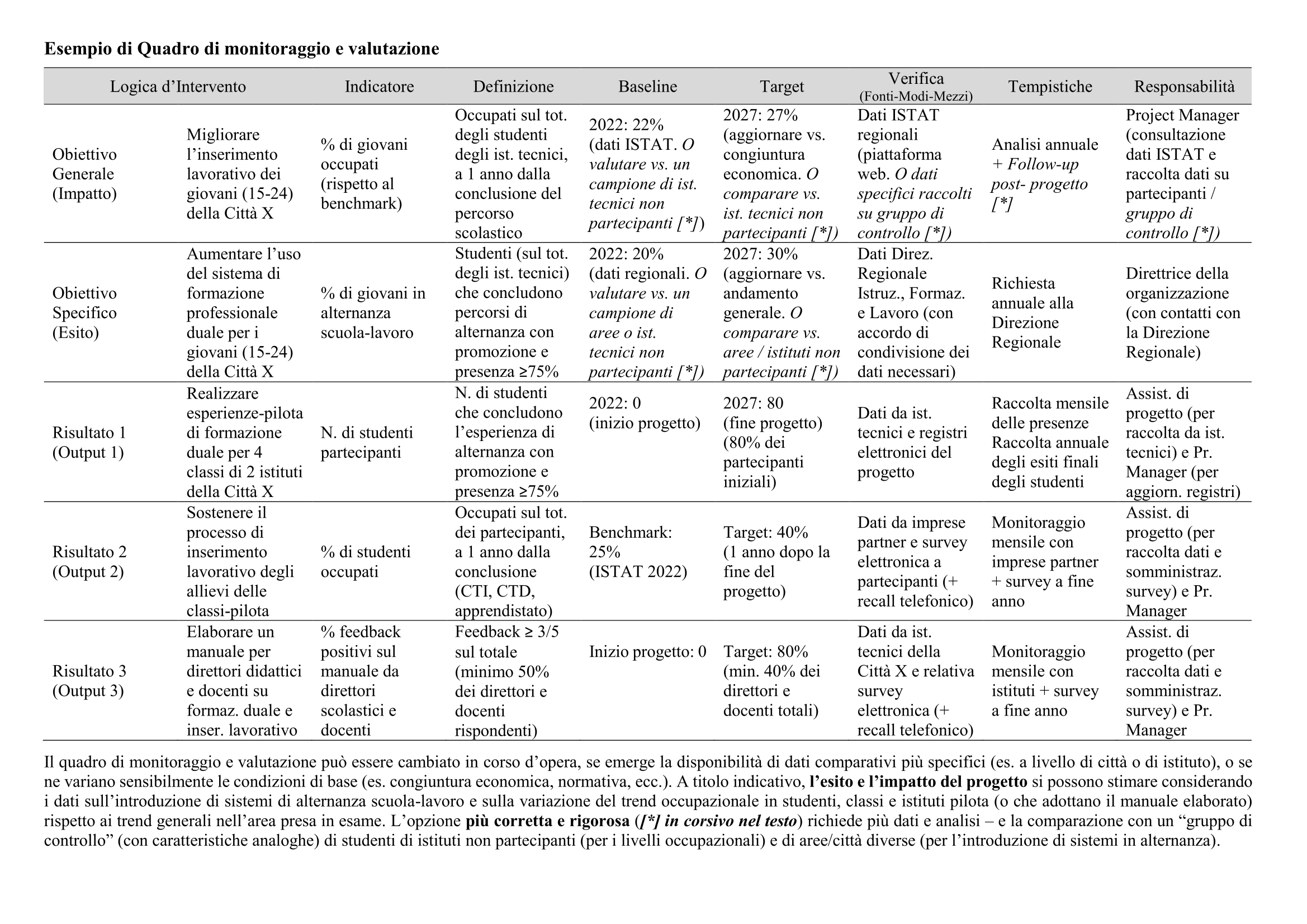

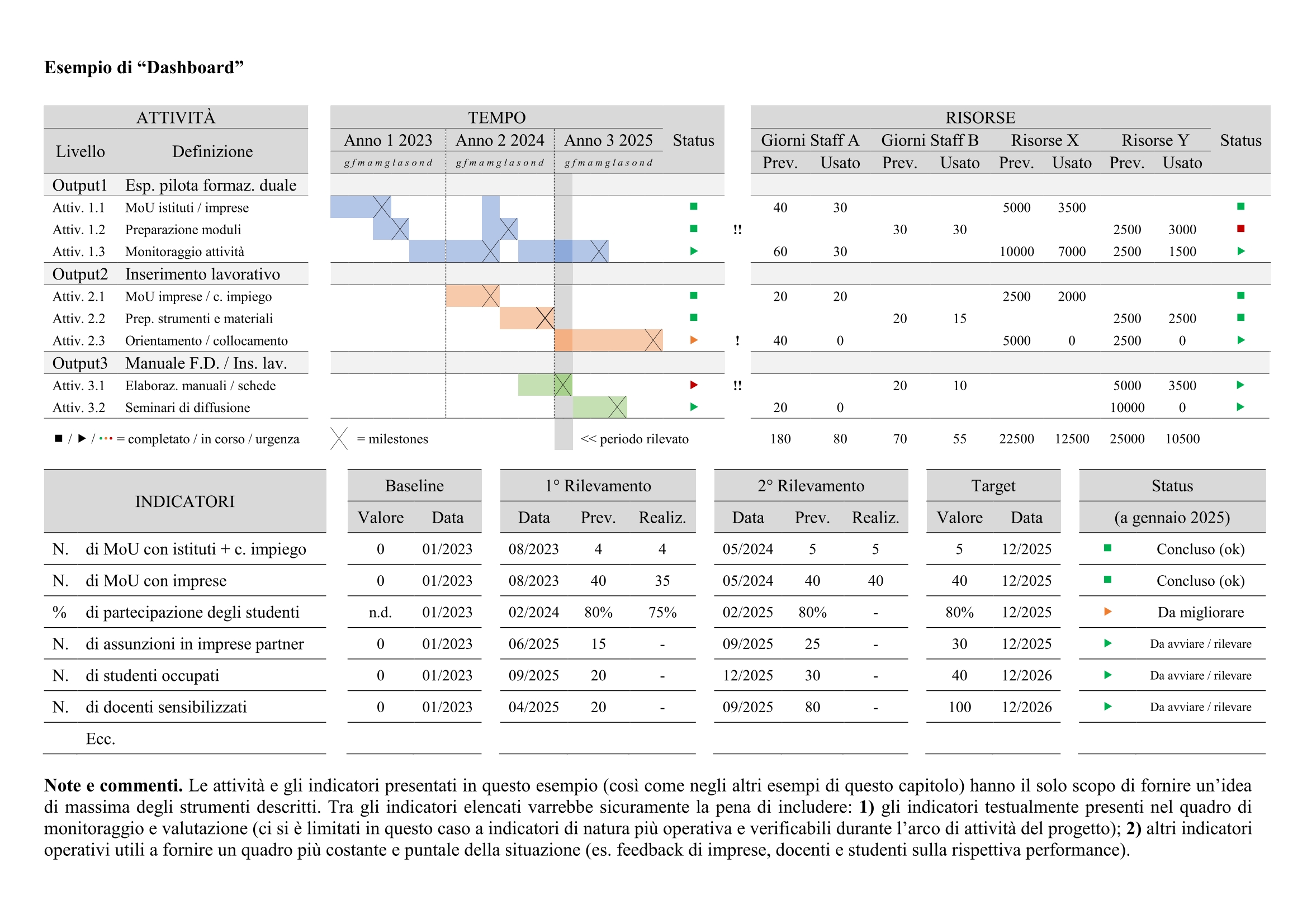

A more detailed and specific example is provided at the end of theMonitoring and Evaluation Framework example.

The choice of comparative metric (or the simultaneous use of multiple comparative references) may vary depending on the availability of data. Differences between “factual data” and “quasi-counterfactual data” can be analyzed (and possibly weighted, or corrected) in light of other factors and variables that may have affected the two reference populations:

- Positive factors – e.g., positive results from parallel initiatives in the local organisations (e.g., vocational courses, support for internships, tools for “matching” labor supply and demand…).

- Negative factors-for example, economic difficulties of enterprises in the local organisations or worsening enabling conditions (e.g., decrease in resources allocated by government to education or social welfare).

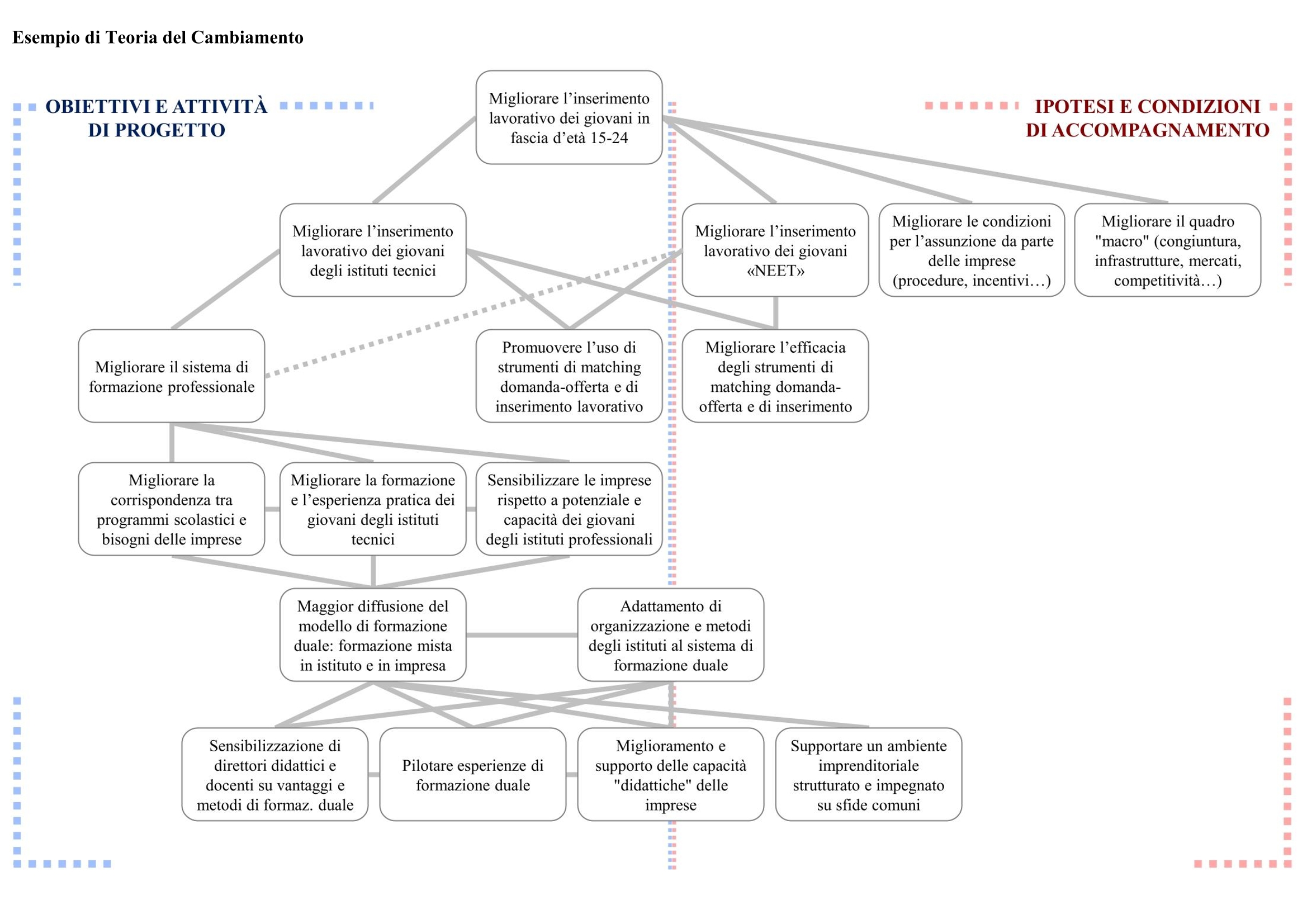

The Theory of Change can assist in this weighting activity, as it provides a “mapping” of all the conditions necessary to bring about a desired change.

In cases where this is possible and the resources are available to do so, it is possible to initiate data collection activities within the scope of the project either on the group of beneficiaries (e.g., youth 15-24 from certain technical colleges) or on control groups that are as similar as possible (e.g., youth 15-24 from the same colleges, similarly distributed in terms of age, class, grade point average, gender, and household income of origin, or youth 15-24 from other technical colleges of the same type and size, located in neighborhoods with similar socioeconomic conditions).

Non-experimental impact assessment methodologies. There are various methodologies that are not strictly quantitative for measuring the impact of a project from its intervention logic, or its theory of change. These are non-experimental methods, which thus have less ambition for “scientificity” than counterfactual methods, but are aimed at formalizing the process of attributing change or observed outcomes to a given project or intervention. We mention in particular:

- Contribution Analysis. This methodology starts with a reasoned and plausible causal theory of how change is believed to occur (intervention logic or theory of change). It then focuses on gathering evidence that validates that theory: looking for other factors that may have contributed to the observed outcomes, identifying and excluding (where possible) alternative or complementary explanations that may have led to those outcomes. To do so, it embraces different perspectives (e.g., context, other interventions, actors’ narratives, beneficiary feedback) designed to suggest different factors or “causal pathways” that may have led to or contributed to the outcome;

- The Global Elimination Methodology (GEM) is based on the systematic identification of possible alternative explanations that may have led to the observed outcomes by drawing up lists of causes and the “modus operandi” linked to them, for each outcome of interest. It is then determined which of the causes occurred and which of the “modus operandi” were observed. Causes for which the relevant “modus operandi” was not observed are discarded, leaving only those causal explanations that have a genuine causal link. From this, the true effectiveness of the intervention can be more accurately contextualized and evaluated;

- Realist Evaluation starts from the consideration that the effectiveness of an intervention depends not only on the cause-effect relationships of what a project or intervention produces, but on a plurality of mechanisms related to the context, the set of actors and a community, their historical, cultural, economic, human and social interactions and dynamics. In different settings and in different communities an intervention will indeed have different outcomes and effectiveness. Evaluation (which draws from quantitative and qualitative sources) thus seeks to map a set of hypothetical “mini-theories of change” that can capture the different dynamics and contextualize in this the intervention and its effectiveness;

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) compares different cases (configurations of possible different causal conditions), but which produced a similar outcome. It therefore analyzes clusters of factors present in different cases, but which produced the outcomes and impacts of interest, to define the degree of significance of each condition in achieving the desired impact, and to identify the simplest set of conditions that can explain all the observed outcomes, as well as their absence;

- Process Tracing is a methodology for examining and testing a specific causal link, to assess whether the evidence is sufficient to draw a conclusion about the cause. It applies four types of tests of increasing “power”: the “straw-in-the-wind” test, which allows one to define whether or not there are conditions to exclude a priori a causal link; the “circle” test, which allows one to exclude a causal link, when the condition analyzed is present, but the expected result is not present; the “smoking gun” test, which, on the contrary, confirms the co-presence (and tendentially, the causal link) of the analyzed condition and the expected outcome; the “doubly conclusive” test allows (in very rare cases) to exclude the existence of other causal links besides the one identified.

Impact as “stories” of change. What has been illustrated so far follows a logical and structured pattern, more or less quantitative, based on the concept of “measuring” the change achieved with respect to and using more or less refined statistical techniques (varying according to the ambitions of “scientificity” of the evaluation process undertaken).

In some projects this scheme may be complex or insufficient to correctly and fully illustrate qualitative changes, unexpected phenomena and effects not defined in the initial metrics. For this reason, there are broader qualitative or untethered methods of measuring impact against initial “goals” (e.g. “goal-free” evaluation).

Again, a comprehensive, exhaustive and rigorous treatment of the topic is beyond the ambitions of this Guide. However, it is important to draw attention to the importance of qualitative and less structured aspects in measuring the impact of a project.

In operational terms, this means asking the following questions: how have the lives of beneficiaries (or beneficiary organizations) changed as a result of the project? What role did the project play in their evolution, their “history,” and their individual experience? In the perception of the beneficiaries (or beneficiary organizations), what would their lives and history have been like without the project intervention? Can these small individual “stories” in turn produce new small and striking “stories of change”? Through individual “stories” and points of view, is it possible to draw a line that identifies the project’s parameters of success and its weaknesses?

“Stories” can be collected and evaluated through various methods of qualitative analysis, already mentioned in the previous sections: interviews and focus groups; case study writing and narrative surveys; and more specific methods, such as“most significant change“ and systems for analyzing and graphing trends and qualitative changes.

This type of analysis adopts an empirical approach based on “induction,” that is, formulating general conclusions from particular cases. It should not be considered a “plan B” compared to other methodologies, as it may be able to capture different, deeper or at least complementary elements than more structured systems of analysis.

Another widely used qualitative assessment approach is theOutcome Mapping, which estimates the effects of a project or intervention through analysis of changes in the behavior, relationships, activities and actions of people, groups and organizations with whom it has directly worked. It is based on the assumption that all social change ultimately depends on changes in human behavior; and that the sustainability of all change depends on relationships among people. From this philosophy flows the object of the relevant evaluation monitoring system: 1) the vision to which the intervention is intended to contribute and (most importantly) the changes in behavior, action, and relationship that are intended to be achieved; and 2) the “boundary partners” of the intervention, i.e., individuals, groups, and organizations with whom the program directly interacts and over whom it has direct opportunities for influence. The resulting analysis is qualitative in nature and focuses on observing (and sometimes self-assessing) the behavior change of those working with the project. Although less rigorous, it can therefore be simpler and more applicable than other approaches.

An analysis through “change stories” of various kinds makes it possible to develop communication and dissemination material that is interesting and usable by a broad audience of specialists (by virtue of its depth of analysis), by partners and stakeholders (who can in turn make it their own and disseminate it), and by the broader audience of laypersons.

These aspects are relevant and appreciated in the context of European projects. Reporting and communication are interrelated aspects that respond to a common goal of accountability and transparency (accountability) towards institutions, citizens and its target community.

Deepen concepts and approaches on impact. For those who wish to address impact measurement and management methodologies in more depth and from alternative and complementary viewpoints, we recommend:

1. BetterEvaluation, a knowledge platform and global community dedicated to the improvement and dissemination of methodologies and tools for good evaluation of projects, interventions and public policies. It proposes in particular a tool(RainbowFramework) to better define and manage one’s own evaluation system, a selection of dedicated Guides, and a detailed description (with examples and an extensive review of in-depth links) of methods and approaches used in the world of evaluation;

2. The Evaluation Manual produced by the European Commission (DG INTPA). It focuses specifically on evaluation procedures and processes used on European projects in third countries, but contains valuable references to how to manage the evaluation process starting with defining the intervention rationale (third chapter, on approaches, methods and tools);

3. TheIPSEE (Inventory of Problems, Solutions, and Evidence on Effects), a dedicated platform curated byASVAPP, the Association for the Development of Public Policy Evaluation and Analysis. It offers a review of the problems that public policies should address, the solutions adopted, and the existing empirical evidence on their effects, accompanied by an impact glossary and an overview of the methods used;

4. Anextensive review of guides and tools produced by specialized organizations in the field of impact investing, to which we have devoted a separate discussion.Impact investing is characterized by a methodical and conscious mobilization of resources to achieve measurable impact in areas where there is a shortage of it (principles of intentionality, measurability, and additionality);

5. A guide developed as part of CIVITAS, a European Union initiative dedicated to urban mobility. Although with examples dedicated to the specific sector, it provides a very clear, comprehensive and general treatment of the topic of project and program evaluation.

6. A “user friendly” project evaluation manual developed in the U.S. (government agency National Science Foundation), which has a systematic, comprehensive and scientific approach to the subject of project evaluation.