NOTES

[1] For more:

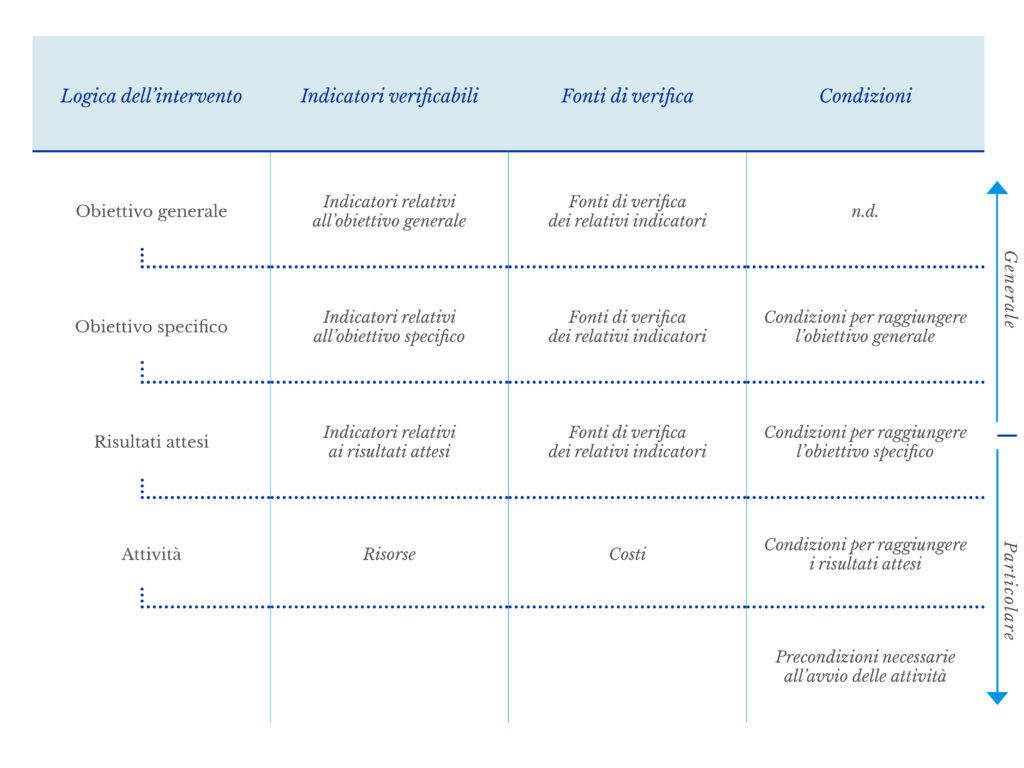

- As we will see later, the model presented constitutes the “basic version” of the logical framework. In fact, it is possible (indeed, recommended) to add columns referring to the starting value of each indicator, the value that we aim to achieve, and the current value recorded at set times in the life of the project, for monitoring purposes. It is also possible to alternatively define the different levels of the intervention logic, i.e., in terms of impact (= general goal), outcome (= specific goal) and output (= expected results or tangible products); and to add “intermediate goals” to the intervention logic. However, since these changes do not change the layout of the “basic model” logical framework but only detail some aspects of it, we prefer to keep a simpler structure for illustrative and illustrative purposes.

[2] For more:

- The upper right column of the logical framework is left blank: in fact, it carries the abbreviation “n.d.” (not available) in the proposed scheme. In a logical framework, the conditions indicate what is needed, along with what is provided by the project intervention logic, to accomplish what is provided at the next, more general level. The expected results are achieved due to the activities and the occurrence of certain conditions, indicated alongside the activities; the specific objective is achieved due to the results and certain conditions, indicated alongside the results; and so on. Since there is no level after the overall goal, there is no need to indicate conditions alongside the overall goal.

[3] For more:

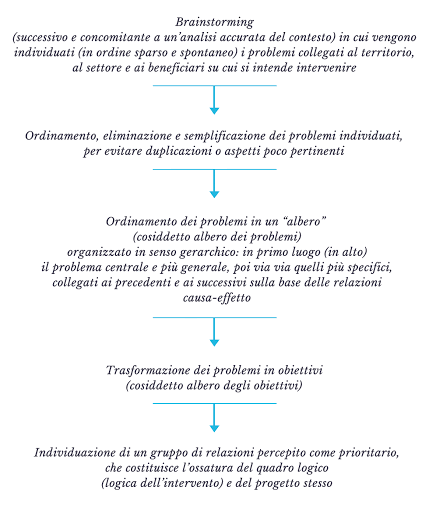

- The process of developing a logical framework does not necessarily follow the order of this description. The description provided in this chapter proceeds logically, from the most general level to the most particular level, from the definition of the intervention logic to the more specific aspects. The process for defining a logical framework, on the other hand, described in the next chapter, may follow a different order: it includes problem and solution analysis, context and stakeholder analysis, defining an intervention strategy, and others.

- A logical framework can be read from top to bottom and left to right, from general to particular, as proposed in the description below. However, it can also be read from the bottom up and from left to right, from the particular to the general: this alternative reading order allows the chaining and coherence of the project logic to be followed from the most specific aspects. The examples below illustrate the main senses of reading a logical framework. Both senses of reading are useful and complementary to structuring a project.

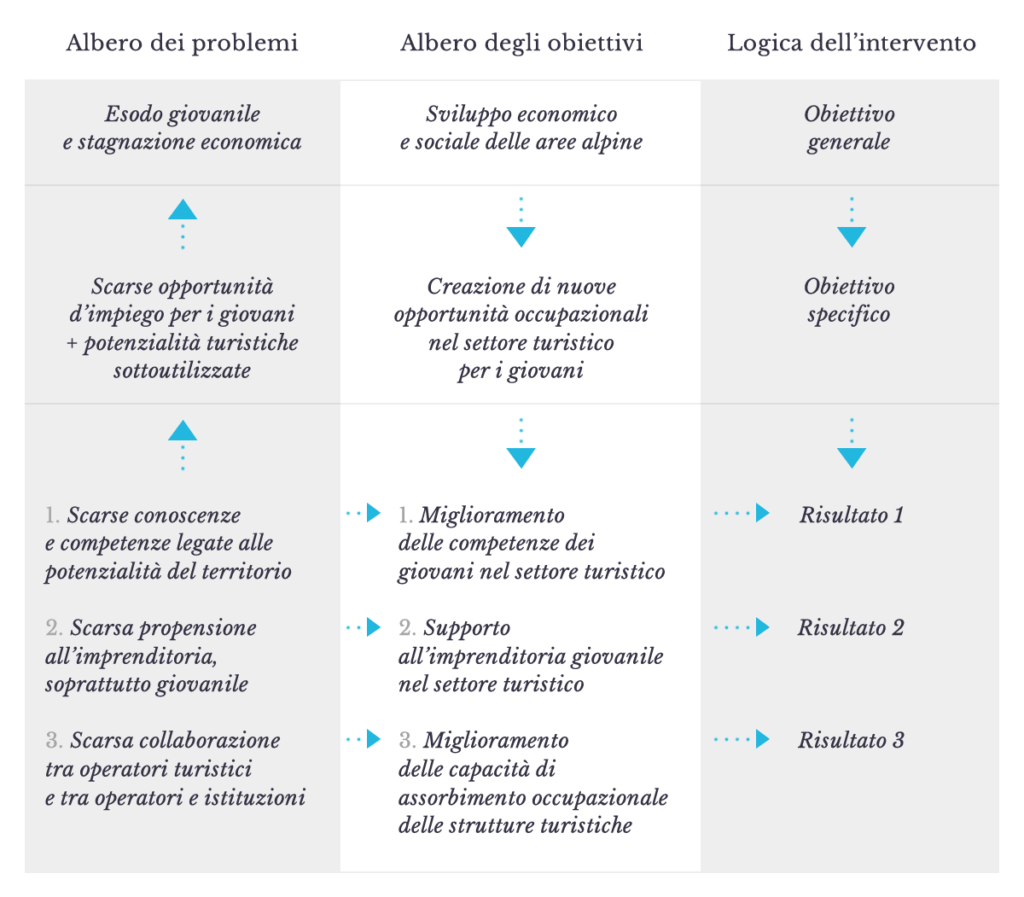

[4] This will be further explored in a section on defining the intervention strategy. [5] For more:

- The more extensive versions of the logical framework, which we will see at the end of the next chapter devote ad hoc columns to these dimensions, to make clear baseline and target-value of each indicator (with reference year of these values) and the value of the indicator at specific points in the life of the project(current value), emphasizing their importance. This increased attention responds to the consolidation of practices and processes in the world of Europrojecting and the need to monitor and prove as rigorously as possible the achievement of project objectives and results: an attitude that is incumbent on EU and national institutions, taxpayers, beneficiary communities and organizations active in the same field.

[6] The lengthy process of debating, reviewing and approving the community budget (devoted mostly to program funding) bears full witness to this. Here a in-depth discussion of this issue.