Types of European funds and programs

An initial overview

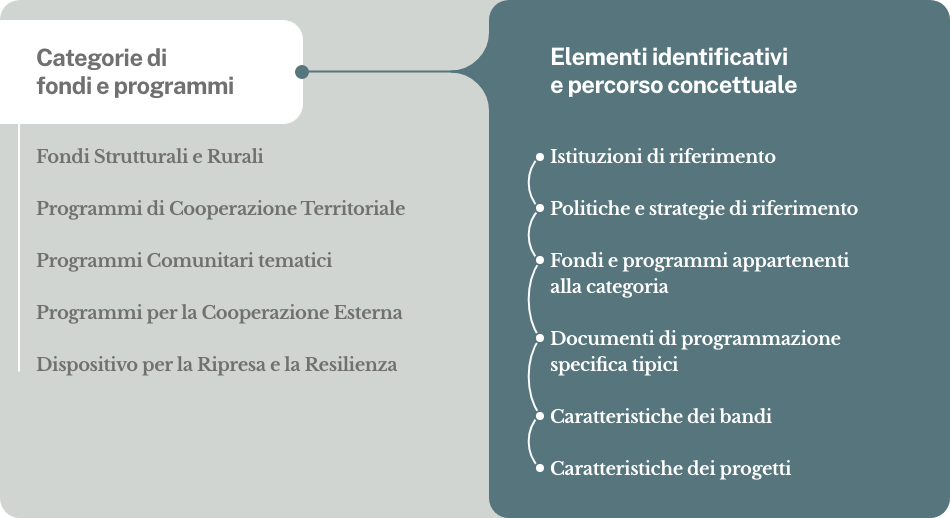

In the previous chapter we traced the conceptual path linking European institutions, legislative acts, policies, strategies, programming documents, calls and projects. In this chapter we provide an initial categorization of community funds and programs, presenting the main identifying elements for each category:

- the institutions of reference,

- the relevant policies and strategies,

- Funds and programs belonging to the identified category,

- the specific planning documents typical of the category,

- characteristics of the calls,

- And finally, the characteristics of the projects.

As explained in the previous chapter, it is important for EU projects and funding activity to be aware of all of these elements in order to best meet the expectations of the funding agency; and thus be able to have greater assurance of success (project allocation) and impact (in the long run).

The following categorization is one of the possible ones: it is useful in understanding the architecture of community funds and programs, but it is not of general and absolute value. For example, our Guide does not have a separate section for programs for external cooperation and the Recovery and Resilience Facility, but it is useful here to discuss their special features. Each fund and program has its own characteristics and, at the same time, common characteristics with those of other funds and programs.

The Structural and Rural Funds

A first major type of European funds, the one considered “closer” to our territories because it is locally managed, is structural and rural funds. As we shall see in the dedicated chapter, each fund has peculiar characteristics, but it is possible here to outline their common features.

- INSTITUTIONS. The DGs in charge of managing structural and rural funds are the DG REGIO (structural funds), the DG EMPL (ESF+), the DG AGRI (rural funds) and the DG MARE (FEAMPA). Management of Structural Funds is shared with regional and national Managing Authorities.

- POLICIES and STRATEGIES. At the “macro” level, structural and rural funds pursue the regional and cohesion policy, the common agricultural policy and the maritime and fisheries policy.. Individual interventions under the Operational Programs (see below) reflect the policy and strategic priorities of individual regional and national Managing Authorities.

- FUNDS and PROGRAMS. The structural and rural funds are the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), The Cohesion Fund, the European Social Fund + (ESF+), the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF), the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (FEAMPA) and the Just Transition Fund (JTF). They are indeed “funds,” and for each of them there is a dedicated line in the community budget. However, in order to be implemented, they need to turn into “programs,” which are developed and managed at the national and regional levels.

- PROGRAMMING. The programming of these funds takes place at two levels, as they are funds with shared management between European institutions (which define their general framework of intervention and priorities) and member states (which follow their specific programming and operational management). For the Structural Funds, there is a Partnership Agreement that identifies general allocations and programming for the whole country, then specific National and Regional Operational Programs ( ROP e NOP ) for specific programming of ERDF and ESF+ funds in the various regions and thematic areas. I Rural Funds provide for regional Rural Development Programs ( RDPS ) and, starting in 2023, a “national CAP strategic plan” that will give coherence to actions financed by EAFRD and EAGF.

- AWARDS. The calls for this category of funds are not accessible through a unified platform, but through the websites of the individual Managing Authorities, namely the national ministries (PON) and the regional directorates in charge of economic development (ERDF), labor and social policies (ESF+) and agricultural policies (RDP).

- PROJECTS. Projects implemented under this category of funds are local in scope, usually regional (ROP) or national (NOP). They can be submitted in Italian and do not require complex or international partnerships. They must be aligned with the relevant policies (see above) and with policies, strategies and actions pursued by national and regional authorities in the relevant issues. They can be inspired by best practices developed in other regional or national contexts.

Territorial Cooperation Programs

Territorial cooperation programs (explored in more detail in a special section of the Guide) represent one of the declinations of the Structural Funds. In fact, they are financed by the ERDF (one of the Structural Funds) and have local Managing Authorities, however acting in a broader sphere: cross-border (straddling a border), transnational (a larger area made up of several regions in different countries) or interregional (local organisations or actors from across the EU united by similar challenges).

- INSTITUTIONS. The DG in charge of managing territorial cooperation programs (funded by the ERDF) is the DG REGIO. Management is shared with regional Managing Authorities in charge of monitoring the different programs in the relevant geographical area (cross-border, transnational or interregional).

- POLICIES and STRATEGIES. At the “macro” level, territorial cooperation programs pursue the regional and cohesion policy EU (such as the ERDF). At the local level, they take up strategic axes identified by regional authorities in the relevant geographical area.

- FUNDS and PROGRAMS. Territorial cooperation programs are funded by the ERDF. They are themselves “Programs” in their own right, as well as one of the “programmatic declinations” of the ERDF, along with ROP and NOP. Each territorial cooperation program belongs to one of three families (cross-border, transnational or interregional cooperation programs).

- PROGRAMMING. The programming of these funds takes place at two levels, as they are funds with shared management between European institutions and member state regions/territories. Territorial cooperation programs are actual programs (similar to ROPs) drawn up by the relevant Managing Authority to plan the use of funds in the relevant (geographic or thematic) area.

- AWARDS. The calls for this category of funds are not accessible through a unified platform, but through specific websites. Normally each territorial cooperation program has its own website, managed by the relevant Managing Authority.

- PROJECTS. Projects implemented under this category of funds are both international (involving multiple countries) and local (involving a specific area) in scope. They are presented in English or a language considered vehicular in the local organisations. They require a more complex and international partnership that demonstrates an appropriate impact on the local organisations. They must be aligned with the EU’s regional and cohesion policy and with policies, strategies and actions carried out in the local organisations and themes of reference by the responsible regional authorities. They can draw inspiration from good practices developed in other regional, national, transnational or European contexts.

Thematic Community Programs.

Directly managed thematic community programs are probably the area of europlanning that we tend to talk about most (including within our Guide) and about which information is most universal and accessible. Indeed, while each has its own unique characteristics, these programs address the “big issues” of interest to European institutions, cover actors from across the European Union, and have a unique reference system (the “Funding and Tenders“). We outline their common characteristics below.

- INSTITUTIONS. Major community programs are followed directly by the various DGs of the European Commission, each responsible for a particular thematic area – and by a number of Agencies charged with their executive management. Sectoral peculiarities, specific needs, and the variety of actors involved generate differences between one program and another, but all DGs pursue a common strategic framework, have gradually standardized their procedures, and use a common portal reference for the management of their calls and projects. For more information on DGs and Responsible Agencies you can refer to the appropriate information given, for each program, in our prospectus.

- POLICIES and STRATEGIES. Given the wide thematic variety of community programs, it is impossible to define a priori the reference policies pursued. Normally, there is a reference policy for each thematic area and sub-area of each of the community programs. Since the technical and thematic aspect is central to this type of program, it is necessary to investigate it in the best possible way, using, for example, the information provided in the previous chapter (section on Reference Policies) and links to the contextual elements provided, for each program, in our prospectus.

- FUNDS and PROGRAMS. Each of the directly managed community programs corresponds to a dedicated line in the community budget . There are many: you can see the details in the appropriate chapter or in the appropriate section of our Guide.

- PROGRAMMING. Each of the directly managed community programs already presents an indicative implementation plan “at source.” In particular, the respective regulations (which are also their legal basis) provide a great deal of information regarding the actions funded, the eligibility and evaluation criteria, the budget dedicated to each line of intervention-and many other details. However, almost all of them present a more specific and accurate planning document, the Work Plan or Work Plan, which normally provides the details of the planned calls from year to year. Regulations and Work Plans can be found in the reference documents section of the Funding & Tenders portal.

- AWARDS. Directly managed community program calls can be accessed through the “Funding and Tenders“, through which most of the information and reference documents can also be accessed. However, it is advisable to consult the websites of the DGs and Executive Agencies of reference for each program, which are very rich in content (technical and thematic) and operational information (information for participation in calls for proposals).

- PROJECTS. Projects implemented under directly managed community programs have a European reach: although they have different structures and modes of operation (here an analysis of the different levels ci complexity) they aim to achieve significant impact and valuable and appreciable “added value” throughout the European Union. They are presented in English and normally require a complex partnership, covering different countries and realities in the European Union. They must be aligned with the EU-level reference policy (or policies) in the specific area and sub-area in which they operate. Each program or call may also refer to several related or complementary policy and strategy areas, which are updated, taken up and renewed with some regularity. Projects should be inspired by and take into account good practices and actions already developed in other contexts throughout Europe, and demonstrate a degree of innovativeness, effectiveness and replicability with respect to what has already been implemented.

Programs for External Cooperation

Programs for external cooperation do not have specific coverage within our Guide. In fact, they represent one of the declinations of thematic EU programs-more specifically, the one dedicated to EU “foreign policy,” emergency response and cooperation and development activities with third countries. However, they have some specific characteristics that differentiate them from other EU programs: 1) they have a strong territorial dimension, that is, they are dedicated to working with, or developing, a particular local organisations; 2) they are managed in a decentralized way, through EU Delegations in third countries, or through management modes indirect (i.e., with funds entrusted to third-country institutions or international organizations); 3) have a project management system that has not yet been fully incorporated into the Funding and Tenders portal (they partially use their own systems).

- INSTITUTIONS. The departments in charge of program management for external cooperation are the DG INTPA (program Global Europe / NDICI), the DG NEAR (program Global Europe / NDICI and program IPA III), the DG ECHO (program Humanitarian Aid) e FPI (the Foreign Policy Instruments Service). In many cases (program-countries), operational management is entrusted to the EU delegations in the beneficiary countries and is sometimes carried out indirectly (management entrusted to institutions in the beneficiary countries or international organizations). Indirect management involves an agreement with the chosen country or organization (Financing Agreement), a financial planning process (Programme Estimate), specific procedures e requirements.

- POLICIES and STRATEGIES. Programs for external cooperation are a manifestation of the EU foreign policy (EU policies in major world regions and bilateral policies with individual countries), of the neighborhood policy , of the enlargement policy , of specific EU development and cooperation strategies ( European Consensus on Development , European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid ), of the EU’s broad overall priorities ( Green Deal , Digital, sustainable development and growth, migration, governance, peace and security…) and a range of policies and strategies in more specific areas (democracy and human rights, education and skills, energy, environment, gender equality, health, urban and regional development, food and food security, peaceful and inclusive societies, sustainable economic growth, water and sanitation, international partnerships). Obviously, policies and strategies relevant to the recipient country also assume important weight, since this is a form of collaboration.

- FUNDS and PROGRAMS. There are three programs for external cooperation, part of the larger “family” of EU programs: the Global Europe (also called NDICI, an acronym for Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument, brings together various geographic and thematic programs from the previous programming period), the IPA III (dedicated to pre-accession countries) and the Humanitarian Aid (for emergency support and management).

- PROGRAMMING. In the programs for external cooperation, specific programming (which already has a fair amount of detail at the level of the regulation and annexes to the regulation) is defined in multi-year Indicative Programs (MIPs, in the English acronym), geographic and thematic, managed separately by DG INTPA e DG NEAR depending on their areas of responsibility; ; and, with even greater detail, in Annual Action Plans or Action Documents (AAPs/ADs), again managed separately by DG INTPA and DG NEAR. The program IPA III presents a single programming framework, and the Humanitarian Aid program proposes Humanitarian Indicative Plans ( HIP ).

- AWARDS. Calls for external cooperation programs have, at least at the moment, a specific publication system, which goes through the portals Webgate o PROSPECT. The OPSYS (used for project monitoring) and the publication of calls are expected to merge into the single portal “Funding and Tenders” in the near future. In the area of Humanitarian Aid, response to calls for proposals can only be made by accredited bodies (having signed appropriate Humanitarian Partnerships) and through a specific system called APPEL.

- PROJECTS. Projects implemented under external cooperation programs have an international scope and are particularly complex, as they can cover very different sectors, must be aligned with the objectives of the European Union and the beneficiary countries (not always perfectly consistent) and are implemented in often difficult contexts. The very definition of EU objectives can follow different and complementary logics in the same funding line or call: foreign policy logics (e.g., mitigating migration flows), logics more properly related to cooperation and development (e.g., promoting democracy and civil society participation), and country-logics (aimed at safeguarding relations with a given country, which can also be important for different factors, such as energy and raw material supplies). They are presented in English or the vehicular language of the recipient country (French, Spanish, or Portuguese) and normally require a partnership that includes technical skills in the relevant field and presence and knowledge of the local context of the recipient country. Projects should be inspired by and take into account good practices and actions already developed in other contexts around the world: in Europe and also in similar contexts in emerging, developing and transition countries.

The Recovery and Resilience Device

The Recovery and Resilience Device has a special place among European projects: it is a special and unique device whose very budget is special and outside the same “normal” community budget. Its modes of implementation are decentralized: they resemble the Structural Funds in this, but follow different logics and modes of execution. We have dedicated a specific news category to insights on the Recovery and Resilience Device and the NRP (the National Recovery and Resilience Plan).

- INSTITUTIONS. The department in charge of managing the Recovery and Resilience Device is the Recovery and Resilience Task Force ( RECOVER ), which operates in close coordination with the DG ECFIN . At the Italian level, the governance of the NRP is articulated as follows: 1) political responsibility and coordination are entrusted to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers and a specific Cabina di Regia, which operate in tandem with the Ministry of Economy and Finance (which specifically expresses a PNRR Manager, in direct contact with the European Commission, and a Central Service for PNRR); 2) operational responsibility rests with central titular administrations, i.e., the ministries responsible for the various subjects in which the various NRP interventions are expressed; 3) some interventions are implemented directly by theHolder Administration, others, however, are entrusted to different Implementing Parties, i.e., to Municipalities and metropolitan cities, regions, local governments and to other public and private bodies. Approximately one-third of NRP resources are entrusted to each of these three categories of actors.

- POLICIES and STRATEGIES. The strategic objectives pursued by the Recovery and Resilience Device and the NRP represent a meeting point between the major priorities of the European Union and the specific agenda of national authorities, various ministries, local authorities and other major stakeholders. On the one hand 1) the Device provides minimum amounts to be devoted to the EU’s main priorities of the seven-year period (especially green transition and digital transformation); and 2) national governments are bound to achieve Milestones and Targets agreed upon with the European Commission and to prove achievement (with a strict timeline). On the other hand, consistency with national policies and strategies is essential, because the NRP has made resources available for reforms and interventions that were in part already planned but long blocked due to lack of funds.

- FUNDS and PROGRAMS. Funding sources represent one of the major innovations of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (which is, as mentioned earlier, a facility external to the community budget proper). Resources are borrowed by the EU on financial markets through the issuance of securities. Part of the resources raised (385 billion) is used to provide loans provided at subsidized rates to member states; another part (338 billion) is used to finance grants administered by member states. Part of the “European debt” thus created is thus returned by the member states, while for the other part new EU “own resources” will be introduced. Funds are disbursed by the European Union to member states in tranches conditional on the achievement of Milestones and Targets. The Italian government provides additional resources (Complementary Plan) to expand the scope of the interventions implemented.

- PROGRAMMING. NRP planning is the responsibility of the central authorities in charge of interventions, viz. the individual ministries, In coordination with the Presidency of the Council and the Ministry of Economy and Finance. The reference site ItaliaDomani allows you to follow the different types of interventions and of reform envisaged under the Plan.

- AWARDS. NRP calls are published in a special section of the ItaliaDomani website, which distinguishes calls launched directly by the titular administrations versus those launched by the various Implementing Entities. The websites of titular Administrations and Implementing Entities naturally remain a very important complementary source of information.

- PROJECTS. The “projects” under the NRP represent, in most cases, infrastructural or otherwise large-scale interventions, although they have a local impact and are largely managed by local implementing entities. The space for interventions of the Third Sector exists, but it is not majority and does not, in most cases, involve classical type projects. Most of the interventions are very specific in nature and in many cases take the form of a tender rather than a grant. The expected impact of the NRP for the Italian Third Sector and territories lies both in direct participation (necessary where possible, in order to benefit from funds that may risk being unused) and, above all, in the beneficial systemic effect of the interventions, investments and structural reforms envisaged under the NRP.